In Lehman’s terms? (Part One- Mise-en-scene)

This 2-part flash (Part Two will be mercifully much shorter) is in recognition of Ben Bernanke & his co-conspirators being awarded The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of A Nobel

In recent weeks we’ve experienced:

The UK bond market meltdown (the GILTantrum)

Increasing currency volatility (the CashCrash)

NGO concerns about the impact of developed market monetary and fiscal policy on weaker socioeconomic groups and emerging economies (Extreme UNCTAD)

Fears of a European banking crisis (Teutonic shift)

In the 1980s, financial deregulation and a reversal of tight monetary policy (the US Federal Funds Rate fell from 20% in 1981 to 8.5% in 1989) enabled rapid growth in credit that increased consumption, indebtedness, corporate profits, inequality and asset prices.

A normal person might see problems with this.

Policymakers however are not normal people and were shocked at the ultimate inability of people and businesses to service ever increasing amounts of debt. By the start of 1990s economies were falling into recession as capital and property markets bubbles crashed around them pricked by the sharp pin of higher oil prices.

A normal person might deduce that encouraging rapid debt build-up hadn’t been sustainable (and that exogenous price shocks might be something to be aware of going forwards).

Policymakers however are not normal people and resolved to combine the miracles of financial engineering with even easier monetary policy (the Fed Funds Rate fell from 8.25% in 1990 to 5.75% in 2000) in order to continue and massively inflate the boom, especially in the most liquidity sensitive assets like the 5,000 or so predominantly technology and growth stocks that had somehow found themselves listed on the NASDAQ. By early 2000, the rapid debt build-up had once again created vulnerabilities that led to a brief recession but a severe day (or 2 ½ years in the case of bubbly dot.com assets) of reckoning.

Once again, the dangers were evident to normal people but not policymakers. By 2003 the Fed Funds Rate had been cut all the way to 1% but having learned their lesson from the Techwreck, policymakers encouraged investment into something as safe (or not) as houses.

Literally.

The property market boom of the noughties inevitably turned into the Great Financial Crisis.

This was no ordinary crisis.

What made it great was the extent to which financial institutions had become so carried away with the elegance of Adjustable-Rate-Mortgages and the ingenious turd-polishing of packaging, slicing and dicing dodgy loan books of Alt-A credit and sub-prime loans into purportedly high-quality Asset-Back Securities which could even be insured to make them even ‘safer’ still.

Except they weren’t.

They were still just highly polished turds.

And when turds encounter gravity, they tend to fall…resulting in a mess splattered over the street….in this case Wall Street.

Initially governments tried to pretend that the mess was nothing to do with them, until the US Treasury and Federal Reserve got together to backstop mortgage specialist investment bank, Bear Sterns. Prior to this, Bear Sterns was known for being the only Wall Street firm involved with failed hedge fund Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) that had refused to contribute to the 1998 plan by the Fed and Treasury to bail out LTCM’s counterparties. Bear Sterns had refused on the basis that LTCM’s counterparties had all got what they deserved by lending to an entity that was over 30 times leveraged.

By 2007 Bear Sterns was almost 37 times leveraged and its assets consisted significantly of turds of various degrees of polishing, meaning that in reality, a strong huff and puff was probably all that was needed to blow Bear Sterns’ house down, or at least into the waiting arms of a shotgun marriage with JP Morgan, presided over by the various regulators.

Wounded at the criticism they received for their role in this, the regulators weren’t going to be made to look so stupid again when Lehman Brothers got into similar trouble.

They were going to let Barclays look stupid by buying Lehman.

Except that one of the most underrated players in the GFC, UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Alastair Darling, refused to put UK Government on the hook for liability risk for the transaction and the deal failed.

As did Lehman Brothers.

As had New Century in America and Northern Rock in the UK and a raft of unpronounceable Icelandic banks who had bought up an inordinate number of other international financial institutions.

As did Washington Mutual and the Royal Bank of Scotland.

As almost did US quasi-government mortgage agencies, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, along with JP Morgan, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch, Wachovia, AIG, Commerzbank, BNP, UBS, Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank who all relied on forms of assistance to come through the crisis.

What this highlighted was the extent of leverage in the system and the reliance on contiguous pools of assets, where one bank’s asset problems would quickly contaminate another, which in turn would contaminate the next.

A normal person would now have been running away screaming from the dangers of leverage, but policymakers are not normal people and decided in their finite and misguided ‘wisdom’ to create government funds to be used to fund the rehabilitation of the financial sector.

The United States did this better than anywhere.

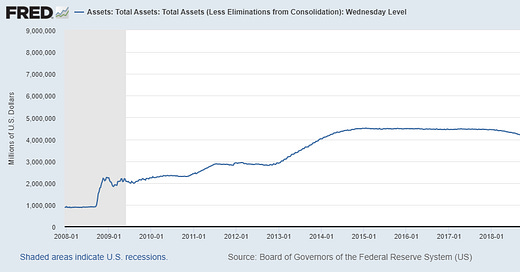

The adoption (the sharp spike up in Federal Reserve assets in late 2008 in the chart below) of aggressive Quantitative Easing (QE) initially resulted in the Federal Reserve buying (and therefore effectively rehabilitating) troubled mortgage securities of banks. The Fed indicated that it would expand its balance sheet to $2 trillion by buying over $1 trillion of ‘assets’. This helped put a floor under US capital markets and stocks, credit, property and treasuries rebounded.

In June 2010, the Fed’s initial programme of buying concluded.

The markets and economic data immediately spat a huge dummy.

By August, the Fed started buying again (QE2):By 2012, US policymakers decided that all bad things have to come to an end and initiated plans to ‘taper’ asset purchases. This went down like a lead balloon with markets and economic participants and pretty soon, the Fed was buying again and promised to keep buying until 2015 (QE3).

Going into 2015, with the balance sheet now at $4 trillion (twice the initial estimate), the Fed again tried to wean markets off QE.

Markets didn’t like this but in a global game of chicken, China blinked first and unleashed an unprecedented (except in America) wave of credit creation, which pump primed the global system….for a while.

In the relatively benign waters of late 2018, the Fed tried reducing its balance sheet (i.e. actually selling some of the stuff that it had bought) and in 2019, the US financial system was seizing up once again. This time (the Reverse Repo Rupture) highlighted a new problem – it’s insufficient for there simply to be enough liquidity….it also has to be in the right places. What was largely seen as a ‘plumbing problem’ (i.e. sufficient funds unable to get to where it’s needed quickly enough) was ‘solved’ by the Fed’s now default policy of more QE (this should have been designated QE4 in case you’re still keeping count but everyone quickly forgot about this because of what happened next).

COVID arrived.

The almost vertical spike in 2020 in the previous chart reflects the policy response to COVID and lockdown. Unlike previous responses, this actually involved putting some money in the hands of citizens and businesses (but still mainly involved jacking up asset prices, primarily benefitting the 0.1% and bank balance sheets), but this was, at last, a small step in the right direction.

Today, that leaves a world where asset prices remain hugely interconnected, massively dependent upon liquidity, have been inflated by government largesse (as opposed to leverage - government debt owed in the government’s own currency isn’t really debt), and vulnerable to exogenous shocks, such as higher oil prices or spiking supply shock inflation.

In our next flash we’ll take a look at why this made GILTs so vulnerable, currencies so volatile, pension funds so worried and whether it poses a risk to financial institutions (spoiler alert…maybe), credit markets (probably), housing markets (very likely) the most liquidity sensitive pseudo assets (think Ark funds, crypto, meme stocks) and of course, isn’t helping beleaguered banks, like Deutsche and Credit Suisse but isn’t posing an existential risk to the Fed (but ironically has technically reduced the Fed to making losses on its asset income book for the first time in many years - although these are not real losses and the Fed doesn’t feel real pain.

MBMG Investment Advisory is licensed by the Securities and Exchange Commission of Thailand as an Investment Advisor under licence number Dor 06-0055-21.

For more information and to speak with our advisor, please contact us at info@mbmg-investment.com or call on +66 2 665 2534.

About the Author:

Paul Gambles is licensed by the SEC as both a Securities Fundamental Investment Analyst and an Investment planner.

Disclaimers:

1. While every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained herein is correct, MBMG Investment Advisory cannot be held responsible for any errors that may occur. The views of the contributors may not necessarily reflect the house view of MBMG Investment Advisory. Views and opinions expressed herein may change with market conditions and should not be used in isolation.

2. Please ensure you understand the nature of the products, return conditions and risks before making any investment decision.

3. An investment is not a deposit, it carries investment risk. Investors are encouraged to make an investment only when investing in such an asset corresponds with their own objectives and only after they have acknowledge all risks and have been informed that the return may be more or less than the initial sum.