More or less intelligent?

After last month's dive into AI (https://mbmg.substack.com/p/ai-ai-oh) we pause to take a look at how real, or at least human, intelligenceaffects financial & economic decision-making...(Part 1 of 2)

More or less?

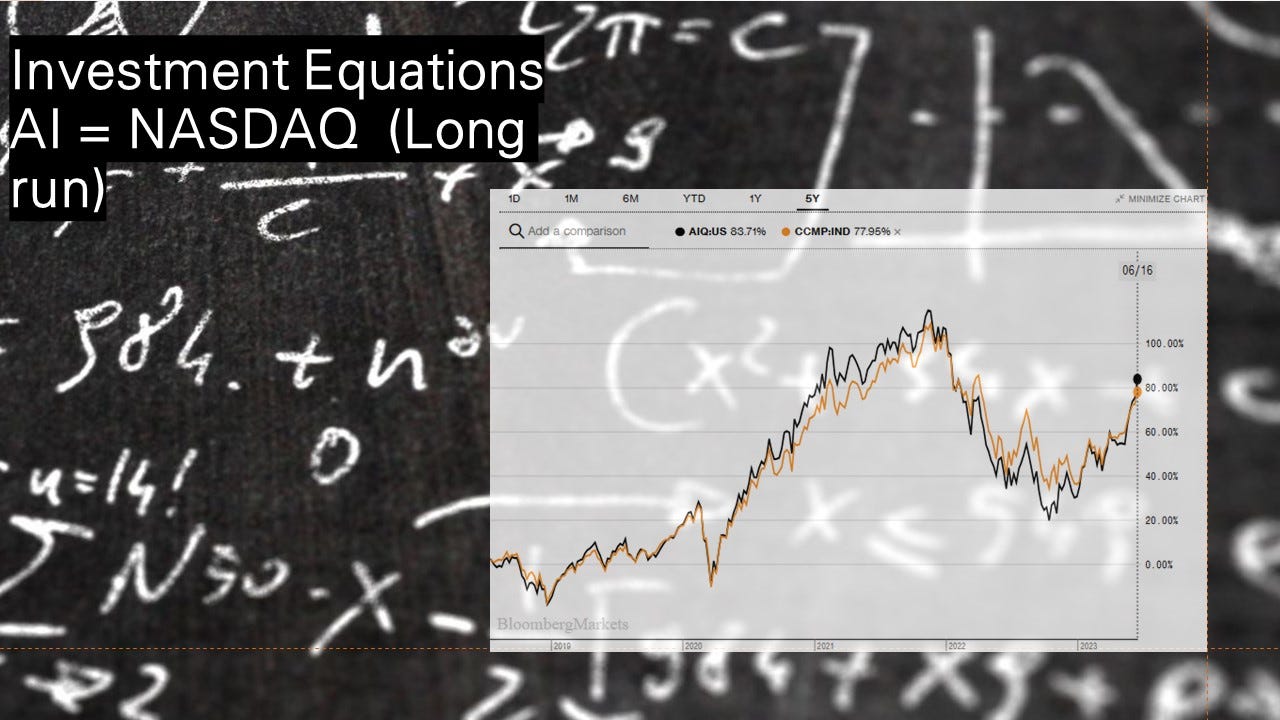

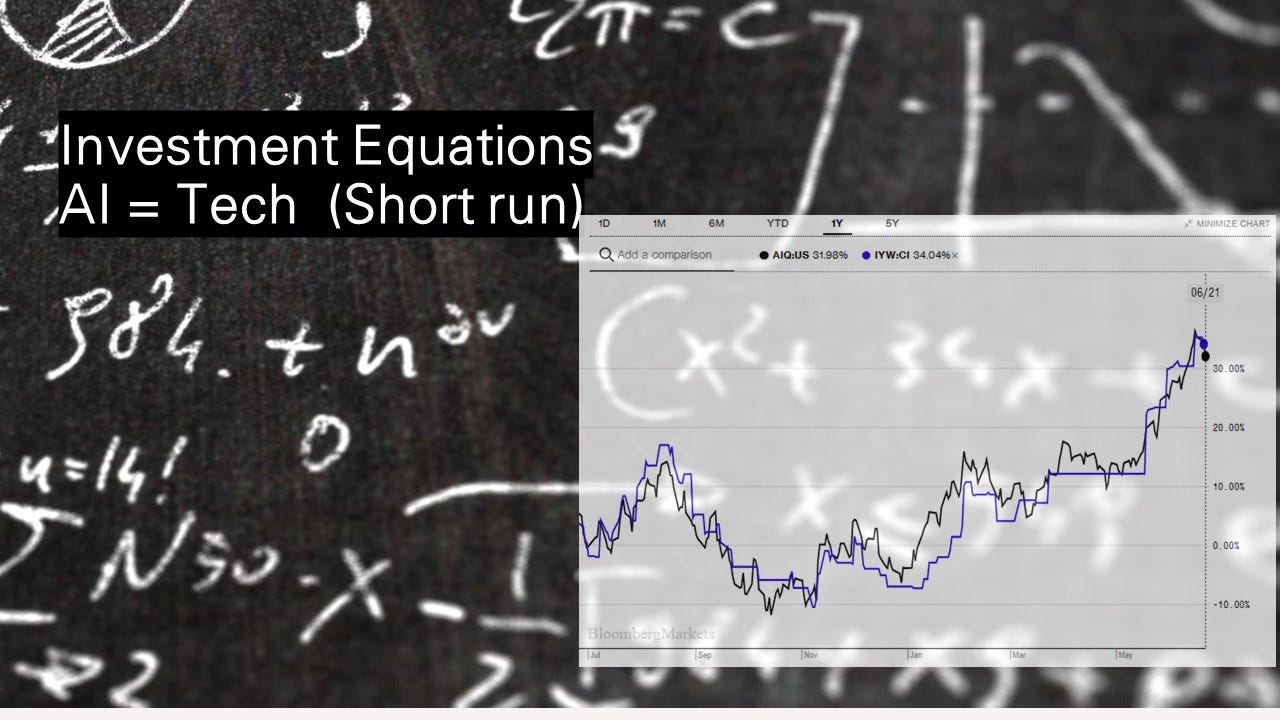

Last month, we investigated whether or not the rise of the AI investment sector constituted a stock bubble.

We concluded that:

· Both AI-related stocks and the broad US growth story had become increasingly overpriced over time

· Both AI and broader US technology had become expensive of late

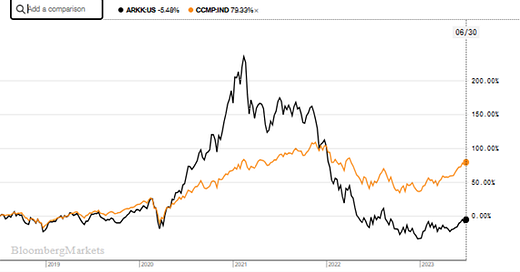

· US growth, US Tech and AI had not reached the exorbitant extents of more obvious bubbles such as Cathie Wood’s ARKK ETF:[1]

This month, we aim to explore human behavioural intelligence to try to understand why bubbles are such a feature of financial and economic systems and why, when the bursting of these bubbles appears so surprising to capital market participants.[2]

AI continually pushes boundaries in areas where equations, inequations, algorithms and formulae can identify patterns within vast sets of data. It is most useful in advancing areas that appear to require judgement whereas in fact it is able to translate variables (typically within contingent, multi-layered boundaries) into outcomes.

AI often exhibits most value when it transforms big data into specific outcomes through what is termed fuzzy logic. Like algorithms, fuzzy logic exploits increasingly complex decision-tree-like processes to arrive at outcomes.[3]

However daunting it may be to try to decode the AI conundrum, this seems much less challenging than trying to decipher the still largely mysterious decision-making processes of the human brain. Researchers have drawn analogies between the human’s brain inductive and deductive reasoning capabilities and AI’s synthesis of computational analysis and fuzzy logic. [4]

Sub-conscious decision-making processes have evolved to encompass both inductive and deductive forms of reasoning.[5] A widely cited example of inductive logic, Occam’s Razor [6] illustrates how general experiences, externalities and individual biases inform inductive judgements rather than the specific details of particular events or issues. This is rooted in our development as cognitive beings who learn from their experiences and apply that learning to help their broad decision-making process. Employing mental shortcuts enables the human brain to decipher and interpret immense volumes of data.

Drowning in Data: Are We Understanding Less While Processing More?

The sheer volume of information that our brains have to process has increased dramatically.

In the 16th century, it's estimated that the brain of a highly educated individual processed around 74 GB of data throughout their lifetime, primarily via reading and audio-visual stimuli. [7] By 1986, even before the ‘internet age’ the average American processed this amount of data every week. Less than a decade ago, it was estimated that this was the average person’s daily data processing load.

Today, we process this volume just in our leisure time each day.[8]

Even more staggering is the sheer volume of data to which we are exposed on a daily basis. Only a small proportion of this is actively processed. The vast majority is absorbed subliminally, often though cognitive shortcuts known as heuristics. Our capacity to absorb such data is understood to be around 250,000 times greater than the volume of data that we actively process.

While these figures are inevitably estimates and subject to continuous revisions, the unmistakable trend is that we are all processing increasing volumes of data, without having any equivalent upgrade in our cognitive hardware. This emphasises both how extraordinarily adaptive the human brain is but also the challenges facing the human neural network. It seems unlikely that we can process this ever-increasing volume with the same degree of efficiency.

Indeed, being inundated with more information doesn’t necessarily translate into better understanding or improved decision-making. In fact, there are compelling reasons to believe that it may hinder comprehension and degrade decision-making capabilities.

Recent research offers novel insights into how our brains manage visual processing. These indicate how the brain effectively filters information in order to avoid overworking or overloading.[9] As data volumes increase, this filtering or editing process necessarily ramps up, . leading us to the paradoxical conclusion that the more we know, the less we might actually understand.

In Part Two of this note, we will try to apply this understanding of human intelligence to explain why we believe that economists and capital market participants are currently exhibiting an even greater misunderstanding of economies and capital markets than the previously high bar that they set. And that is without even considering the inherent biases and self-interest that also help to foster what Mackay termed the ‘Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds’[10]

Even as you read this, you might ask yourself are you are understanding or processing or merely absorbing. Consciously applying that to all information could prove deeply rewarding, albeit impossibly and thoroughly exhausting.

MBMG Investment Advisory is licensed by the Securities and Exchange Commission of Thailand as an Investment Advisor under licence number Dor 06-0055-21.

For more information and to speak with our advisors, please contact us at info@mbmg-investment.com or call on +66 2 665 2534.

About the Author:

Paul Gambles is licensed by the SEC as both a Securities Fundamental Investment Analyst and an Investment planner.

Disclaimers:

1. While every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained herein is correct, MBMG Investment Advisory cannot be held responsible for any errors that may occur. The views of the contributors may not necessarily reflect the house view of MBMG Investment Advisory. Views and opinions expressed herein may change with market conditions and should not be used in isolation.

2. Please ensure you understand the nature of the products, return conditions and risks before making any investment decision.

3. An investment is not a deposit, it carries investment risk. Investors are encouraged to make an investment only when investing in such an asset corresponds with their own objectives and only after they have acknowledge all risks and have been informed that the return may be more or less than the initial sum.

[1] From late 2020 to December 27th, 2022, the Ark Innovation ETF fell by over -80.9%.

[2] We aim to look beyond the pathways that have already been so well trodden by Nicholas Nassim Taleb’s works such as Fooled by Randomness (2001) and The Black Swan (2007) which provided groundbreaking insights into interpretative approaches to randomness, probability and uncertainty.

[3] Fuzzy logic in its most basic sense is developed through decision tree type analysis. Thus, on a broader scale, it forms the basis for artificial intelligence systems programmed through rules-based inferences. Generally, the term fuzzy refers to the vast number of scenarios that can be developed in a decision tree-like system. Developing fuzzy logic protocols can require the integration of rule-based programming. These programming rules may be referred to as fuzzy sets since they are developed at the discretion of comprehensive models. Fuzzy sets may also be more complex. In more complex programming analogies, programmers may have the capability to widen the rules used to determine the inclusion and exclusion of variables. This can result in a wider range of options with less precise rules-based reasoning….The concept of fuzzy logic and fuzzy semantics is a central component to the programming of artificial intelligence solutions. Artificial intelligence solutions and tools continue to expand in the economy across a range of sectors as the programming capabilities from fuzzy logic also expand. IBM’s Watson is one of the most well-known artificial intelligence systems using variations of fuzzy logic and fuzzy semantics…..Although it has a wide range of applications, it also has substantial limitations. Because fuzzy logic mimics human decision-making, it is most useful for modelling complex problems with ambiguous or distorted inputs. Due to the similarities with natural language, fuzzy logic algorithms are easier to code than standard logical programming, and require fewer instructions, thereby saving on memory storage requirements. These advantages also come with drawbacks, due to the imprecise nature of fuzzy logic. Since the systems are designed for inaccurate data and inputs, they must be tested and validated to prevent inaccurate results. Fuzzy logic is often grouped together with machine learning, but they are not the same thing. Machine learning refers to computational systems that mimic human cognition, by iteratively adapting algorithms to solve complex problems. Fuzzy logic is a set of rules and functions that can operate on imprecise data sets, but the algorithms still need to be coded by humans. Both areas have applications in artificial intelligence and complex problem-solving….An artificial neural network is a computational system designed to imitate the problem-solving procedures of a human-like nervous system. This is distinct from fuzzy logic, a set of rules designed to reach conclusions from imprecise data. Both have applications in computer science, but they are distinct fields” - https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/fuzzy-logic.asp

[4] Voskoglou, M.Gr. (2020) A philosophical treatise on the connection of scientific reasoning with Fuzzy Logic, MDPI. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7390/8/6/875.

[5] “Inductive reasoning involves starting from specific premises and forming a general conclusion, while deductive reasoning involves using general premises to form a specific conclusion.” www.dictionary.com/inductive-vs-deductive

[6] Occam’s razor is a philosophical principle named after 14th century Franciscan friar, William of Ockham. “Suppose an event has two possible explanations. The explanation that requires the fewest assumptions is usually correct.”

[7] This is reckoned to be the equivalent of watching around sixteen movies.

[8] It’s important to note, as stated, that these figures are all estimated in various ways and that there is great divergence in the estimates produced by different experts, as can be seen from this sample –

Agarwal, P. (2021) Sway: Unravelling unconscious bias. London: Bloomsbury Sigma

Kwong, E. and Agarwal, P. (2020) Understanding unconscious bias, NPR. https://www.npr.org/2020/07/14/891140598/understanding-unconscious-bias.

Reber, P. (2010). https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-is-the-memory-capacity/.

Wu, T. et al. (2016) The capacity of cognitive control estimated from a perceptual decision-making task, Scientific reports. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5034293/

[9] Manassi, M and Whitney, D https://theconversation.com/everything-we-see-is-a-mash-up-of-the-brains-last-15-seconds-of-visual-information-175577 .

[10] Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds is described by www.goodreads.com as “an early study of crowd psychology by Scottish journalist Charles Mackay, first published in 1841”. It charts several historic instances of financial ‘delusion’ including the South Seas Bubble and the Tulip Bubble. We strongly recommend it as insight and entertainment although not strictly as objective historical record. –

“In reading the history of nations, we find that, like individuals, they have their whims and their peculiarities; their seasons of excitement and recklessness, when they care not what they do. We find that whole communities suddenly fix their minds upon one object, and go mad in its pursuit; that millions of people become simultaneously impressed with one delusion, and run after it, till their attention is caught by some new folly more captivating than the first.” – Preface to Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds