Beyond Numbers: The Search for Meaning in a Data-Driven World

Chasing Dreams Beyond Wealth: A Market's Quest for Meaning

“My love has got no money, he's got his strong beliefs

My love has got no power, he's got his strong beliefs

My love has got no fame, he's got his strong beliefs

My love has got no money, he's got his strong beliefsWant more and more, people just want more and more

Freedom and love, what he's looking for” - Freed from Desire by Gala Rizzatto

In an age where data reigns supreme, the timeless lyrics of Gala Rizzatto's "Freed from Desire" echo a profound truth: the most steadfast convictions are not bound by the weight of gold or the count of coins.

As we grapple with the complexities of financial markets and the deluge of data that promises but often fails to clarify, we are reminded that true understanding often lies beyond the reach of numbers.

This article seeks to unravel the paradox of information overload in our economic systems and the cognitive dissonance it creates in our quest for meaning and informed decision-making.

Section 1: The Cognitive Mirage in Economic Forecasting

In the complex world of economic forecasting, behaviour often overrides logic, shaping market sentiments.

Behavioural factors help to explain why market participants’ expectations of market outcomes are so often confounded. This highlights the particular shortcomings of applying inductive forms of reasoning to financial forecasting. Additionally, while shortcuts or heuristics enable the human brain to decipher and interpret immense volumes of data, this can also create a tendency to unreliable processes that lead to incorrect assumptions. The proliferation of data has led us to conclude that in many aspects of life, we are all drowning in data without having adequate tools to fully understand this sheer volume of information. (Gambles, Aug 2023)

“Even more staggering is the sheer volume of data to which we are exposed on a daily basis. Most of this is not actively processed. Instead it is absorbed subliminally, often though cognitive shortcuts known as heuristics. Our capacity to absorb such data is understood to be around 250,000 times greater than the volume of data that we actively process. While these figures are inevitably estimates and subject to continuous revisions, the unmistakable trend is that we are all processing increasing volumes of data, without having any equivalent upgrade in our cognitive hardware. This emphasises both how extraordinarily adaptive the human brain is but also the challenges facing the human neural network. It seems unlikely that we can process this ever-increasing volume with the same degree of efficiency. Indeed, being inundated with more information doesn’t necessarily translate into better understanding or improved decision-making. In fact, there are compelling reasons to believe that it may hinder comprehension and degrade decision-making capabilities. Recent research offers novel insights into how our brains manage visual processing. These indicate how the brain effectively filters information in order to avoid overworking or overloading.[1] As data volumes increase, this filtering or editing process necessarily ramps up, . leading us to the paradoxical conclusion that the more we know, the less we might actually understand.”

Section 2: Sovereign Debt Through the Cognitive Lens

Drowning in data, we lose sight of clarity—especially with sovereign debt. As countries juggle loans and payments, a flood of indicators and analyses often obscures, rather than illuminates, our fiscal view.

One aspect to which this applies is sovereign debt. Despite These conversations also prompted the following review of the history of US Sovereign indebtedness. This was written prior to listening to two of the episodes that Bloomberg’s Tracy Alloway and Joe Weisenthal at the Kansas City Fed’s annual symposium.[1] In many ways, that’s unfortunate because it would have saved a great deal of time to simply suggest that readers listen to the discussion between Tracy, Joe and economic historian Barry Eichengreen and then just assume the complete opposite of Eichengreen’s comments.[2]

What did Eichengreen say that was so wrong?[3]

In our view, it's wrong to minimise, as Eichengreen did, the financial and economic risks of US geopolitical aggression. While there is no obvious alternative to Dollar hegemony in the short-term, the costs of imposing this (in terms of financial costs, military costs and fractured international relations) are rising dramatically, while the benefits to USA of the system are potentially diminishing. In a sense, this is how all empires end – the need for continued expansion of its financial footprint is as much of a long-term danger to the US system, as the need to expand physical footprint was to the various empires that it succeeded. The European empires of former times found themselves with no new worlds to conquer in the 20th century and were faced with peaceful acquiescence to post-colonialism or catastrophic war leading to the same result.

In our view, it's also wrong to simply dismiss other (non-USA) political systems as authoritarian.

The myth of American freedom ignores the constraints imposed by the American system on the people.

This in turn leads to an assumption that all is well with the American socio-economic and political system and that the polarization which Eichengreen finds so distasteful is both at historically egregious levels and is exogenous.

In fact, as Noam Chomsky has shown, it's a persistently recurrent deliberate design feature of the system.

It's also wrong in our view for Eichengreen to commend his Jackson Hole central bank audience for doing such a great job of bailing out the US and western financial systems but then criticising them for not seeking to force Main Street to pay off the ‘debt’ incurred in these bail outs.

Eichengreen displays a neoliberal, neoclassical economics misunderstanding of how sovereign debt actually works. He wrings his hands because, quite rightly, he wants to address US infrastructure deficiencies and climate change challenges but believes that this won’t be done, simply because American people and businesses haven’t ‘repaid; the additional ‘debt’ that has underwritten Wall Street for the last 2 decades or more. When Tracy Alloway tried to challenge this in MMT terms, Eichengreen dismissed this, with a specious misdescription of the US monetary system and processes.

Section 3: Historical Perspectives on U.S. Sovereign Debt

As stated, our own analysis prompted us to draft the following brief history of US Sovereign financing and monetary and fiscal policy.

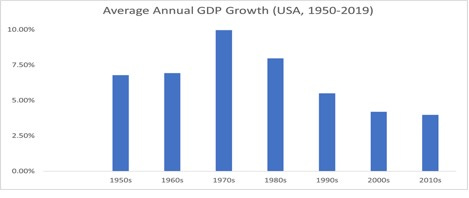

It remains our view that the main fundamental driver of long-term US interest rates has really been a “referendum on what long-term US growth rates are going to be” but in the short-term rates have been driven higher by a confluence of Chinese and Japanese selling and increasingly disproportionate issuance of long-term notes by the US Treasury. We believe that this has created investment opportunities in long-term treasuries.

This opportunity is being hugely augmented by the secondary effect of herd effects, creating a false level of confidence in risk assets. Not only did the best part of $1 trillion flow into the most liquidity-sensitive assets, but this created a ripple effect where additional capital also flowed out of the least liquidity-sensitive assets, chasing the bubble, what Argonaut Capital’s Barry Norris has termed “the dash for trash”.

This led us to take a step back to try to recap on how we actually got here..

The Genesis of U.S. Debt - The War of Independence and the birth of a nation

The first US ‘debts’ were effectively incurred prior to the formal ratification of the new country, with the Continental Congress racking up huge bills and issuing IOUs during the War of Independence. At that stage the Congress lacked the power to impose taxation or levy duties. These can therefore, unlike today’s government outlays, be considered genuine borrowing obligations, which potentially undermined the new country following its founding. [2]

A disproportionate amount of debt was incurred by what were to become the Northern states. Part of the agreement by which the new Federal Government assumed these debts involved accepting that the seat of the new government be located further south, where the new states had much lower indebtedness. Hence the location of US Government in swampland that was to become the District of Columbia, on the border between Maryland and Virginia. James Swan, a wealthy Scots-born Bostonian financier, arranged to assume the French debt and re-sell it, at higher interest rates, to wealthy private American investors in 1795. Swan later died in debtor’s prison in Paris.[3]

The fledgeling country, influenced by the policies firstly of Treasury Secretary Hamilton (the eponymous hero of the musical Hamilton) and then by those of Jefferson, typically ran significant budget surpluses by imposing high duties. Revolutionaries who had rallied around the mantra of no taxation without representation were discovering just how expensive representation could be. Opposition was often forceful, such as the Whiskey Rebellion of Pennsylvania in 1794.

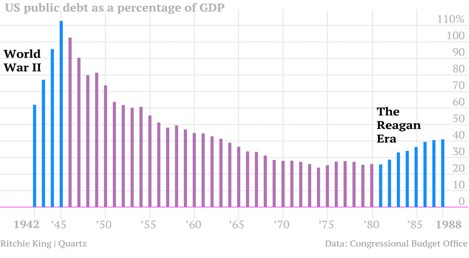

Perceived to be on a sounder footing, USG was able to tap international debt markets to fund ongoing adventures, such as the ‘Louisiana Purchase’ in 1803. The first blip in this early trend (see the chart below) came about due the costs of waging the war of 1812, but by 1835, US Federal ‘Debt’ was fully repaid and remained at low levels until the Civil War, when ‘debt’ surged 40-fold from $65 million in 1860 to almost $ 2.8 billion in 1866.

From Civil War to World War

Prior to the Civil War, government financing had largely relied on duties but the war also heralded the introduction of income taxes, although these were repealed once the ‘debt’ started to fall again (as a proportion of GDP, which is the modern way to compare equivalence over time, but wasn’t in usage at the time).

Government revenues (America at the time adopting a combination of high levels of duties and extreme degrees of protectionism) remained strong and, as the chart below shows, continued falling until the outbreak of and America’s entry into World War I, which, as in many countries, was financed by selling bonds and war bonds into the domestic market.

The Roaring Twenties and the Great Depression

World War I marked a sea change in that the post-war Republican-dominated administrations focused on reducing taxes (especially for the wealthiest and highest income earners). The post-war era also saw the emergence of American dominance in many areas of commerce and manufacturing. Together, these factors resulted in a dramatic volte face from the aggressive protectionism on which American development had been founded to the adoption of free-market policies that better suited America’s new-found post-war relative status as top dog.

One consequence of the changes in the American economy and in USG policymaking was the adoption of policy structures that might be viewed as the prototype of the debt ceiling approach which has become an annual hamstrung bone of contention.

The combination of tax cuts for the wealthiest, the antecedents of austerity policies for the masses and an obsession with reducing the national debt during the 1920s played a large role in creating the breeding ground for the Great Depression. By 1932, the Roosevelt administration sought to reverse this by providing greater fiscal support to the economy to try to combat the worst ravages of the Great Depression.

Too early reduction in government support during the mid-1930s reduced the effectiveness of ‘The New Deal’ but by the end of the decade, the spectre of World War II was posing an even bigger threat to USG finances.

The Second World War

In many ways, the seeds of the new deal only fully took root following World War II. The growth in the US economy following World War II resulted in a lower debt-to-GDP ratio without penalising the majority of Americans in the way that the policies of the 1920s had done, with post-war economic expansion continuing until well into the 1960s and 1970s:

However, by the 1980s the lessons of the 1920s had been completely forgotten and America once again repeated the mistakes of the past, this time re-badged as ‘Reaganomics’, once again fostering economic inequality, along with higher levels of private debt and financial instability.

A brave new world? Or just another ill-informed one?

By now, the Dollar was well-established as the global reserve currency but the groundbreaking attempts of economist Hyman Minsky and his intellectual heirs, including Michael Hudson and Steve Keen, to explain the actual functioning of the US economy were mainly falling on deaf, neoclassical ears of a largely Republican establishment. One such realisation that has been largely ignored was the awareness that US Treasury bonds are not really a form of debt so much as a form of interest-bearing currency. [4] Once it is understood that the US Government (and its agencies) has monopoly rights over Dollar creation it becomes apparent that, especially since the abolishment of the gold standard in 1971, there are no financial reasons that can cause America to ‘default’ on either its currency or its US-Dollar denominated debt.

The present is very different to the past.

In 1795, default was a distinct possibility.

During the period when the value of the Dollar was linked to gold, then the increasing risk of not being able to offer convertibility to gold of Dollars in existence was certainly at least a theoretical possibility. Since Nixon ‘closed the gold window’, abolishing convertibility of Dollars to gold in 1971, the Dollar eco-system is effectively a closed loop, in that USG actually has no need to borrow to fund expenditure. The Treasury can create Dollars in whatever form it chooses– coins, Dollar bills, Treasury bills or bonds. It suits US policymakers to exert economic control by influencing short-term lending rates by continuing to issue interest bearing currency, in the form of treasury bills and treasury bonds. Judging by the amount of ill-informed fearmongering that we see in our email inboxes, this point seems to be one of the most widely held misunderstandings in modern finance. We plan to delve more into examining what form of Dollars policymakers have issued of late and what that means for markets and the economy.

In the end, as we stand on the precipice of economic futures shaped by past debts and present decisions, the intersection of cognitive science and historical perspective offers us a unique vantage point. It is here, at the confluence of understanding and experience, that we might find the wisdom to navigate the uncertain waters of tomorrow's markets.

What are your thoughts on the relationship between data saturation and economic understanding? How do you see the historical patterns of U.S. debt influencing future fiscal policies? Join the conversation below, and if you find these reflections insightful, please share this article with your network.

[1] The event has been held at the Jackson Lake Lodge in Wyoming in August each year since 1981. The venue was chosen to attract then Fed Chair, Paul Volcker to attend, because of his known predilection for the excellent fly-fishing in the Wyoming’s Grand Teton National Park at that time of year. We regard it as something of an echo chamber and pejoratively describe it as the Fed talking out of its Jackson Hole. However, issues discussed at Jackson Hole can influence future economic policy and also financial markets (last year’s event saw comments by current Fed Chair Jerome Powell spook markets). Fortunately, this year, Powell was both briefer and less controversial.

[2] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-08-29/barry-eichengreen-on-living-in-a-world-of-higher-public-debt

[3] Eichengreen is a respected economic historian who has produced some excellent comparative studies (e.g. analysing the GFC relative to the Great Depression) but this episode, based on his paper presented at this year’s Jackson Hole symposium was more of a personal op-ed.

[4] https://mbmg.substack.com/p/dazed-and-confused

[5] It’s worth remembering that one factor that coloured British attitudes towards American independence was the view that, unlike the colonies in for instance the West Indies, there was little worth fighting for in terms of valuable natura resources in America. However, the strategic value of the colonies waging war against the British Empire was sufficiently attractive that the French Government and Dutch lenders were willing to advance loans to fund what they might have viewed as a proxy war to weaken Britain.

[6]https://gratefulamericanfoundation.org/who-paid-off-the-2024899-u-s-national-debt-today/

[7]This is well explained in Stephanie Kelton’s book ‘The Deficit Myth’.